Phyllis Nagy: Carol and me

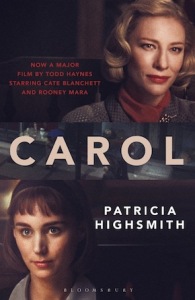

by Mark Reynolds Carol. StudioCanal” width=”360″ height=”239″>Carol, starring Cate Blanchett as a wealthy 1950s New York housewife and mother who risks her place in society by embarking on an intense affair with Rooney Mara’s shop girl, is a hot tip for big prizes as the film industry gears up for its annual awards season. The film, directed by Todd Haynes, is based on Patricia Highsmith’s second novel, originally published as The Price of Salt in 1952 under a pseudonym. The book became a runaway bestseller, and was remarkable for its time in that it allowed for the possibility of a happy ending to a lesbian romance. But it was only acknowledged publicly by Highsmith, and published under her own name, a few years before her death in 1995. I spoke to screenwriter Phyllis Nagy directly after a screening at the London Film Festival. She began by relating the lucky encounter that saw she and Highsmith become friends.

Carol. StudioCanal” width=”360″ height=”239″>Carol, starring Cate Blanchett as a wealthy 1950s New York housewife and mother who risks her place in society by embarking on an intense affair with Rooney Mara’s shop girl, is a hot tip for big prizes as the film industry gears up for its annual awards season. The film, directed by Todd Haynes, is based on Patricia Highsmith’s second novel, originally published as The Price of Salt in 1952 under a pseudonym. The book became a runaway bestseller, and was remarkable for its time in that it allowed for the possibility of a happy ending to a lesbian romance. But it was only acknowledged publicly by Highsmith, and published under her own name, a few years before her death in 1995. I spoke to screenwriter Phyllis Nagy directly after a screening at the London Film Festival. She began by relating the lucky encounter that saw she and Highsmith become friends.

PN: I met her when I was a researcher at the New York Times in the late ’80s when she was in New York to promote Found in the Street. The Times wanted someone to do an article, a walking tour of Green-Wood Cemetery, in which there are some notorious gangsters and other infamous New Yorkers. The person they wanted to do it wasn’t available and they asked for suggestions and I said what about Patricia Highsmith? She happened to be in New York and she happened to say yes, and so for my trouble they sent me to go with her. And that was the start of a very interesting friendship over the last decade of her life.

MR: At that point how much of her work had you read?

I’d read whichever Ripley books were available – I guess the last one hadn’t yet been published – and I’d read Edith’s Diary and Deep Water, and that was it.

Cate Blanchett is so good it’s almost unfair… it’s about being so attuned to what your playing partner is doing, that she’s actually enabling that performance, it’s quite astonishing.”

So what originally attracted you to adapting this novel?

I think it was because I thought there was a way to translate it to cinema rather than take dictation from it. The book was written by Pat in two weeks in a fever dream, and there is no characterisation to speak of. That’s what fascinated me. Carol is a ghostly figure who is the object of desire, and that I think is the right choice for the novel because we get to imagine whoever we like, and that’s very powerful. But film is a much more literal medium, so not only do we need real flesh-and-blood characters with lives, we need something that isn’t interior. The book is point-of-view Therese: we read her thoughts, primarily. There’s not a lot of plot. What there is, is related objectively, you know: “And then I heard that Carol went through a terrible custody battle…” which is great for my purposes, because it gave me free rein.

Presumably you didn’t lift much dialogue from the book.

No, I think I took one line, possibly two from the novel. One is “My angel… flung out of space.” It’s the thing most of the novel’s fans remember; it’s an odd thing to say anyway, and I liked it. But the dialogue in the novel is novelistic; there’s something about the rhythms of it that struck me as not being right for screen. Many people seem to think screenplays are 120 pages of just dialogue, but that’s the least of it. Any monkey can write a line of dialogue, more or less. The book presented an opportunity to do things that you rarely get to do on a big studio movie, namely to be subtle, to write elliptically, and largely on the level of subtext rather than someone saying, “Hey, I think you’re hot!” And the period, of course, allows us to do it, and affords the chance to build a structure on scenes of visual behaviour.

There have been a number of producers and directors attached to this project over the best part of two decades. At what point did you come onboard?

I was the first to come onboard. Pat had been dead for at least four years, I think, and a producer on the project at the time had the rights to the novel and came knocking at my agent’s door to ask who could do this, and my agent said, “Phyllis should do this, she knew Pat,” and that was the start of a rather extraordinary journey. I guess the constant throughout would be Film Four, they paid for all the script development no matter who was in charge, and when Tessa Ross took over there, she kept it going. There was a point, probably around 2010 – so it had been going on for quite a while – when the original producer lost the rights to the book, and I thought, “OK, that’s that.” I was a bit relieved actually, because it’s draining to have to go through all those fits and starts. Anyway, about a year later I got a call from the same agent saying Elizabeth Karlsen, who I’d made a movie with earlier, had bought the rights. She obviously was aware of Carol because I knew her and I’d told her about all the false starts, and she said, “OK, let’s do this.” And I said, “No, I’m tired of this. Good luck, God bless you, I hope you make a great movie, get another script” – because no one else owned the script but me at that point – and eventually she and Tessa just wore me down and I said, “OK, I’ll do it.” And of course I’m very happy that I relented.

The dawn of the Eisenhower administration was a very interesting time. It was supposed to herald a period of prosperity, of trust, of openness, and it was exactly the opposite.”

Karlsen recruited John Crowley to direct, who in turn secured Cate Blanchett and Mia Wasikowska for the main roles; but that team fell apart when it became clear that neither Crowley nor Wasikowska were available to shoot at the same time as Blanchett. Then when Karlsen got chatting to her producer friend Christine Vachon, who was overseeing a Todd Haynes project whose star had just dropped out, there came a lightbulb moment…

Carol. StudioCanal” width=”199″ height=”300″>

Carol. StudioCanal” width=”199″ height=”300″>

Yes, there was a scheduling conflict. That’s often code for somebody got dumped, but this time there really was a scheduling conflict, and again I thought, “OK, here it goes again, terrible, terrible.” And then Todd agreed to do it. I don’t think anyone was certain that he would because he’d never directed anything he hasn’t written. But he agreed to do it, and things then started moving quickly. I did another rewrite based on some of his observations – you always do a rewrite based on conversations with the director – and it was a year and a half from the point that everything fell into place to the shooting. The process with Todd was very quick. He was interested in having the framing device that opens and closes the film, so we talked about that and I went away and wrote a version of it that I thought would work, and that was that. Luckily we were on the same page about tone and things that were important, things that weren’t, and so it was an easy, painless process. I think it’s because he’s written his own work and he’s worked with other people on that work, and he’s sensitive to it. And really, he’s smart enough to know when it needs something. He’s a director who knows the difference between ego and need, and it was a pleasure working with him.

Ed Lachman’s work with Todd Haynes on the cinematography, and the production and costume design of Judy Becker and Sandy Powell brilliantly evoke the 1950s zeitgeist. How did you go about immersing yourself in the period while you were writing?

First of all, the novel is set slightly earlier than the screenplay. The book was published in 1952, but she wrote it set in the very late ’40s. So two things: late ’40s fashions? Verboten. And then the dawn of the Eisenhower administration in 1952–53 was a very interesting time. It was supposed to herald a period of prosperity, of trust, of openness, and it was exactly the opposite, so when I did my adaptation that’s when I set it. I don’t like things that contemporise – either in dialogue or in the psychology, which is far more important to a piece like this. I was determined not to have late 20th-century, now 21st-century attitudes and mores inform how those characters behaved. And that was the trickiest thing over the years, because there were lots of people who would say, “But wouldn’t she feel guilty…?” about this or that. And I’d stress that one of the great things about the book is that it isn’t about gay guilt. It’s about many other types of interference, but not that. So I would say those are the two things that I tried to address in tackling that particular moment in time.

The soundtrack is peppered with atmospheric songs from the period. Were you listening to that kind of music as you were writing too?

Oh, sure. When I write I always suggest music, and there are songs that remain, like the Jo Stafford number in the car, ‘You Belong to Me’, and certain others. Then when Todd came onboard he and a couple of other people drew in some more unusual period stuff, not just hits of the era. And the way that works with Carter Burwell’s score is beautiful too.

Carol. StudioCanal” width=”300″ height=”200″>Which actors’ performances would you say nailed your original vision, or brought unexpected nuances?

Carol. StudioCanal” width=”300″ height=”200″>Which actors’ performances would you say nailed your original vision, or brought unexpected nuances?

You could say all of them, for both questions. But really, Cate Blanchett is so good that it’s almost unfair… You tend to take her for granted, but what she’s doing is not only creating a world or a life for her character, but she is supporting Rooney Mara’s level of gaze and stillness. I don’t want to say Cate’s doing all the heavy lifting, she’s not, but it’s about being so attuned to what your playing partner is doing, that she’s actually enabling that performance, it’s quite astonishing. And Rooney Mara I think will surprise people who are only familiar with her Dragon Tattoo and some of her beautiful supporting work where she’s like a little chameleon. This is so nuanced and so difficult, perhaps that will be a revelation for some people. If I could have Kyle Chandler in everything I do, I would be happy for the rest of my life. It would’ve been very easy to have an actor come in and do a macho number on Carol’s husband Harge. It’s not in the writing, but it would’ve been easy to just barrel through it. He found all the nuance. My favourite moment in the whole movie is a scene in their kitchen where he’s fixing some plumbing and they’re having a fight about the kid, and Therese is hovering in the other room, it’s awful, and he comes out and says to Therese, “How do you know my wife?” And the way he delivers all the raw emotion in that moment, that surprises me, that he got it in one. He’s great. Sarah Paulson does amazing work as Abby with little snapshotty things. Her scene in the diner where she’s telling Therese what happened between her and Carol, it’s just exquisite.

You were recently named as one of ‘ten writers to watch’ by Variety. Do you welcome the pressure that brings?

Well now I do, now that this is successful! It’s always very strange, that kind of thing. I mean it’s nice, you get to go to a festival and get a dinner and meet nine other writers that you may or may not be friendly with in the future. In this case I met someone I really, really liked. But it could all go pear-shaped, couldn’t it? It still could.

What are you doing next?

I’ve just finished another adaptation of The Luneburg Variation, which is an Italian novel by Paolo Maurensig from the ’90s, for Colin Firth and his company. It’s – how to describe it? – it’s a Holocaust revenge thriller set in the world of international chess.

So you’re not about to pigeonhole yourself?

Yes, that’s exactly why I did it. Because I do like difficult novels. This is a philosophical novel about, well, impossible things, so that was a good challenge. Also there were no women in it at all. So I’ve just done that and I think they’re gearing up to film it, and I’ve taken on a writing job for an American studio which is an adaptation of a German debut thriller, The Trap by Melanie Raabe. It differs from most thrillers in that yes, there’s a woman in peril, but she’s on her own, there’s no man to get her out. It’s a strange book about a reclusive writer who hasn’t left her house in twelve years since her sister’s murder. It’s being published in English in the spring, and that will be a whole other kind of experience. And then I’m gearing up to do my next movie as a writer-director, which will be about the last 18 months in the life of the Welsh actress Rachel Roberts.

Is that an adaptation of sorts as well? Are you working from a biography?

No, I was approached by the people who own the rights to her estate, and I had access to her diaries. It’s an extraordinary, extraordinary tale, and I’ve got Rachel Weisz signed up for that. So we’re in the early days of getting money, but who knows, it could be another ten years away.

Phyllis Nagy is a screenwriter, director and playwright. She wrote and directed the HBO film Mrs Harris (2005), which was nominated for 12 Emmys, including best screenplay and best director. Her plays have been performed around the world, including a stint as writer-in-residence at the Royal Court Theatre in London, where she was appointed by then artistic director Stephen Daldry. Born and raised in New York, she is now based in LA.

Phyllis Nagy is a screenwriter, director and playwright. She wrote and directed the HBO film Mrs Harris (2005), which was nominated for 12 Emmys, including best screenplay and best director. Her plays have been performed around the world, including a stint as writer-in-residence at the Royal Court Theatre in London, where she was appointed by then artistic director Stephen Daldry. Born and raised in New York, she is now based in LA.

@PhyllisNagy

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

Carol is on general release from Friday 27 November

facebook.com/CarolFilm

@CarolMovie

@StudioCanalUK

instagram.com/carolfilm